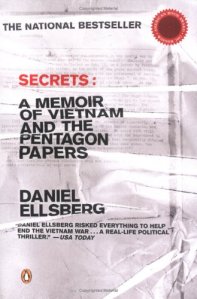

Some powerful excerpts from Daniel Ellberg’s book on Vietnam and the leaking of the McNamara study on US decision making in Vietnam that came to be known as The Pentagon Papers (freely available online by the US National Archive)

Note: Page numbers are from the Penguin edition ISBN 978-0-14-200342-8

p.41: Proof that the US have been capable of global-range drone missions at least as early as the early 1960s:

One morning just before eight o’clock John (ed: McNaughton) came back from McNamara’s office minutes after he’d gotten a call and dashed out. He said to me, “A Blue Springs drone has gone down in China. Bob is seeing the press at eight-thirty. We have ten minutes to write six alternative lies for him.”

It was the only time I remember the actual word “lies” being used. Blue Springs was the code name for an espionage program for reconnaissance photographic flights by unmanned drone planes.

p.213: On the responsibility of people who do not actively oppose wrongdoing:

Nearly all evildoing, she pointed out, like nearly all coercive power, legitimate and illegitimate, depends on the cooperation, on the obedience and support, on the assent or at least passive tolerance of many people. It relies on many more collaborators than are conscious of their roles; these include even many victims, along with passive bystanders, as in effect accomplices.

p.237: Ellsberg’s advice to Henry Kissinger on the psychological and behavioural effects of secret clearances on people:

“Henry, there’s something I would like to tell you, for what it’s worth, something I wish I had been told years ago. You’ve been a consultant for a long time, and you’ve dealt a great deal with top secret information. But you’re about to receive a whole slew of special clearances, maybe fifteen or twenty of them, that are higher than top secret.

“I’ve had a number of these myself, and I’ve known other people who have just acquired them, and I have a pretty good sense of what the effects of receiving these clearances are on a person who didn’t previously know they even existed. (ed: emphasis in original) And the effects of reading the information that they will make available to you.

“First, you’ll be exhilarated by some of this new information, and by having it all – so much! incredible! – suddenly available to you. But second, almost as fast, you will feel like a fool for having studied, written, talked about these subjects, criticized and analyzed decisions made by presidents for years without having known of the existence of all this information, which presidents and others had and you didn’t, and which must have influenced their decisions in ways you couldn’t even guess. In particular, you’ll feel foolish for having literally rubbed shoulders for over a decade with some officials and consultants who did have access to all this information you didn’t know about and didn’t know they had, and you’ll be stunned that they kept that secret from you so well.

“You will feel like a fool, and that will last for about two weeks. Then, after you’ve started reading all this daily intelligence input and become used to using what amounts to whole libraries of hidden information, which is much more closely held than mere top secret data, you will forget there ever was a time when you didn’t have it, and you’ll be aware only of the fact that you have it now and most others don’t… and that all those other (ed: emphasis in original) people are fools.

“Over a longer period of time – not too long, but a matter of two or three years – you’ll eventually become aware of the limitations of this information. There is a great deal that it doesn’t tell you, it’s often inaccurate, and it can lead you astray just as much as the New York Times can. But that takes a while to learn.

“In the meantime it will have become very hard for you to learn (ed: emphasis in original) from anybody who doesn’t have these clearances. Because you’ll be thinking as you listen to them: ‘What could this man be telling me if he knew what I know? Would he be giving me the same advice, or would it totally change his predictions and recommendations?’ And that (ed: emphasis in original) mental exercise is so torturous that after a while you give it up and just stop listening. I’ve seen this with my superiors, my colleagues… and with myself.

“You will deal with a person who doesn’t have those clearances only from the point of view of what you want him to believe and what impression you want him to go away with, since you’ll have to lie carefully to him about what you know. In effect, you will have to manipulate him. You’ll give up trying to assess what he has to say. The danger is, you” become something like a moron. You’ll become incapable of learning from most people in the world, no matter how much experience they may have in their particular areas that may be much greater than yours.”

p.254: On the arrogance of power plaguing the US administration:

There was some realistic basis for the belief that many Vietnamese were naive and misled in their notions of what a Communist-led victory would do for them. But as I now realized, we American officials were no less ignorant or self-deceptive, in turn, about the nature of French rule or of the various Saigon regimes we supported or imposed later or the incentives that would lead people to take up and persist in armed struggle against greatly superior forces – and above all, about the burden of the war on the rural population. In any case, to presume to judge what was best for them, with life and death at stake, was the height of imperial arrogance, the “arrogance of power,” as Senator Fullbright later called it.

p.269 On the difficulty of stepping out of line and doing something you believe in for the first time:

Something very important had happened to me. I felt liberated. I doubt if I could have explained that at the time. But by now I have seen this exhilaration often enough in others, in particular people who have just gone through their first action of civil disobedience, whether or not they have been taken to jail. This simple vigil, my first public action, had freed me from a nearly universal fear whose inhibiting force, I think, is very widely underestimated. I had become free of the fear of appearing absurd, of looking foolish, for stepping out of line.

p.289 On how the Thai Khac Chuyen murder case blew the lid off Ellsberg’s passive tolerance of official lies and helped him decide to do something about it:

I lay in bed that Tuesday morning and thought: This is the system that I have been working for, the system I have been part of, for a dozen years – fifteen, including the Marine Corps. It’s a system that lies automatically, at every level from bottom to top – from sergeant to commander in chief – to conceal murder.

That described, as I had come to realize from my reading that month, what that system had been doing in Vietnam, on an infinitely larger scale, continuously for a third of a century. And it was still going on. I thought: I’m not going to be a part of it anymore. I’m not going to be part of this lying machine, this cover-up, this murder, anymore.

It occurred to me that what I had in my safe at Rand was seven thousand pages of documentary evidence of lying, by four presidents and their administrations over twenty-three years, to conceal plans and actions of mass murder. I decided I would stop concealing that myself. I would get it out somehow.

p. 394 On the surveillance capabilities of the FBI in the 1970s. We can only imagine how much this has changed, in the favour of the government, in our current era of pervasive wholesale surveillance:

The main secret to avoid being found by the FBI (in the 1970s) seemed to be: Don’t use your home or office phone.

[…]

On one occasion, “Mr Boston” went downstairs and across the street to a phone booth on the corner, about fifty yards from the apartment building where were staying that afternoon. He talked for about ten minutes to my friends Lloyd Shearer in Los Angeles, relaying some questions I had for Shearer, who was giving me advice on whom to deal with in the media. We happened to be looking out the front window when he left the booth and came back. Just as he entered the front door, perhaps twelve minutes from the time he placed the call, four police cars converged on the phone booth from two directions. Brakes screeched, and police jumped our with guns drawn, though the booth was now empty. Evidently Shearer’s line was tapped.

p.413 A glimpse into the administration’s psyche and why leaking hard evidence hurts their license to do whatever they want. It’s not so much the content of the leaks – but bringing to light the fact that the administration will sometimes be wrong. That’s why accountability, checks and balances at all levels are important:

H. R. Haldeman to President Nixon, Oval Office tapes, June 14, 1971, on the impact of the Pentagon Papers:

To the ordinary guy, all this is a bunch of gobbledygook. But out of the gobbledygook comes a very clear thing: you can’t trust the government; you can’t believe what they say; and you can’t rely on their judgement. And the implicit infallibility of presidents, which has been an accepted thing in America, is badly hurt by this, because it shows that people do things the president wants to do even though it’s wrong, and the president can be wrong.

p.418 People who have lost touch with reality casually discussing mass murder from their ivory tower – the Oval Office:

Two hours later, at noon, H. R. Haldeman and Ron Ziegler joined Kissinger and Nixon:

President: How many did we kill in Laos?

Ziegler: Maybe ten thousand – fifteen?

Kissinger: In the Laotian thing, we killed about ten, fifteen…

President: See, the attack in the North that we have in mind… power plants, whatever’s left – POL [petroleum], the docks… And, I still think we ought to take the dikes out now. Will that drown people?

Kissinger: About two hundred thousand people.

President: No, no, no… I’d rather use the nuclear bomb. Have you got that, Henry?

Kissinger: That, I think, would just be too much.

President: The nuclear bomb, does that bother you? … I just want you to think big, Henry, for Christsakes.

p.426 The (disgusting) light side of mass murder:

[…] the president was particularly concerned that the bombing of Cambodia in early 1969 and later (code-named Menu, for a series of raids initially code-named Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner) might be about to be revealed.

p.428 How the system of secrecy was used to mislead Congress and to hide entire bombing campaigns:

Moreover, Congress, which had to appropriate the money for these operations, had been given false top secret documentation on what country they were paying to bomb. Hundreds of military staffers in MACV and CINCPAC headquarters were kept busy faking classified flight plans and after-action reports of the bombing raids, falsifying the coordinates of the actual targets to indicate they were in South Vietnam rather than in Cambodia. When in 1970 Nixon ordered secret bombing of the Plain of Jars in Laos (which had no relation to infiltration routes), he used the same system of dual bookkeeping he had used to conceal the bombing of Cambodia.

[…]

A modern president’s practical ability to drop secretly several hundred thousand tons of bombs in a country with which we were not at war was a considerable tribute to the effectiveness of the postwar secrecy system. It gives our presidents a capability to initiate and escalate a war in secret that was scarcely possessed by monarchs of the past.

p. 431 James Madison‘s words on the importance of an informed public:

A popular government, without popular information or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy; or, perhaps, both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance: And a people who mean to be their own governors, must arm themselves with the power knowledge gives.

p.457 Powerful closing remarks of an excellent book:

As Judge Byrne in Los Angeles was issuing his dismissal of our indictment, which had been anticipated all morning in the Oval Office discussions, the president addressed the situation in anguish and perplexity:

For example, on this national security thing, we have the rocky situation where the sonofabitching thief is made a national hero and is going to get off on a mistrial. And the New York Times gets a Pulitzer Prize for stealing documents… They’re trying to get at us with thieves. What in the name of God have we come to?

What we had come back to was a democratic republic – not an elected monarchy – a government under law, with Congress, the courts, and the press functioning to curtail executive abuses, as our Constitution envisioned.